“Rene, what a man, what a violin, what an artist!

Franz Liszt

Heavens! What sufferings, what misery, what

tortures in those four strings!”

Before his fame as a composer, Liszt toured Europe as a child prodigy. Growing up in a lower-class family in Hungary, Liszt could have only dreamt of the journeys he would take through Romantic-era Europe if his faithful father, Adam Liszt, had not devoted himself to his son. Adam, who personally taught Liszt the piano in their humble cottage in the small town of Raiding, eventually sent his talented young son to Vienna for coaching from the esteemed pianist Carl Czerny, and later accompanied him on performance tours across Europe. The funding for these journeys came from wealthy Hungarian nobles whom Adam Liszt managed to convince after his son performed at a salon in the palace of the Esterházys. The Esterházys were perhaps the most significant Hungarian noble family, whose Nikolaus II famously supported Haydn, Beethoven, and Hummel financially.

However, in 1827, Adam Liszt passed away from typhoid fever. Devastated and alone in his musical endeavors, Liszt navigated the complex Parisian society as a newcomer. Soon, however, he would make a major breakthrough in his art. In 1832, Liszt had an epiphany after attending Niccolò Paganini’s concert at the Paris Opera House. An infamously talented violinist, Paganini took the European world by storm with his exceptional technique and compositions, all the while pioneering the concept of a touring musician. Whenever a piece was thought to be impossible, Paganini came and performed it with perfect accuracy and musicianship. Thought to have sold his soul to the devil in exchange for “devilish” fingers, Paganini impressed Liszt so much that Liszt would vow to become a comparable virtuoso as Paganini on the piano. Liszt would increase his practice time to up to 14 hours a day, and from this technical refining would arise the two legendary sets of Paganini études.

The first set of études, called Études d’exécution transcendante d’après Paganini, S.140, was published in 1838. The études followed the trend started by Robert Schumann in 1831. This set translates the virtuosity of Paganini into the keyboard. Though S.140 is forgotten in exchange for the more popular 1851 Grandes Études de Paganini, S.141, the early set contains many beautiful moments not present in the revision. Indeed, the results are just as impressive, if not more so, than the original melodies the set of études is based upon. Endless tremolos and leaps seem to demand hands of titanic size and fingers of arachnid-like mobility. Though catalogued as original Liszt works, the Paganini études are in nature much closer to transcriptions, offering very little new thematic material.

The first etude, Tremolo, was composed using the melody of Paganini’s sixth caprice, but it begins and ends with excerpts from the fifth caprice. The rumbling left-hand and lyrical right-hand melodies echo the original violin composition, but add layers of depth and range that the four stringed instrument cannot produce. The texture intensifies until the fifth caprice melody returns with thunderlike arpeggios and scales, finally concluding with a victorious doubled tonic. The individual hands imitate a violin duet, clearly paying tribute to the original Paganini study. In the first version from 1838, an ossia is present which inco.rporates Schumann’s Op. 10 no. 2. This ossia is not present in the later version from 1851.

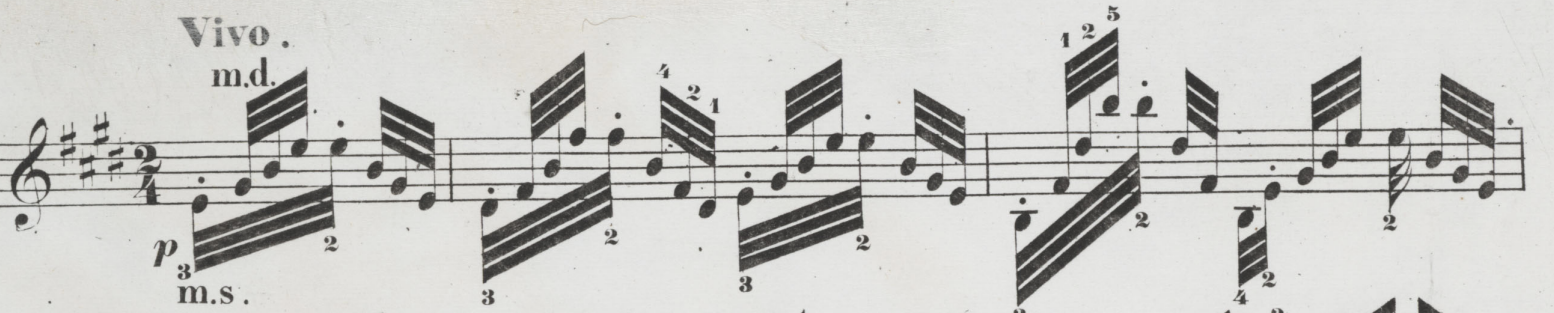

The second etude uses Paganini’s seventeenth caprice and employs extensive use of rapid octaves. Glistening descending runs in the second half stand out against occasional periods of relative musical ease and quiet.

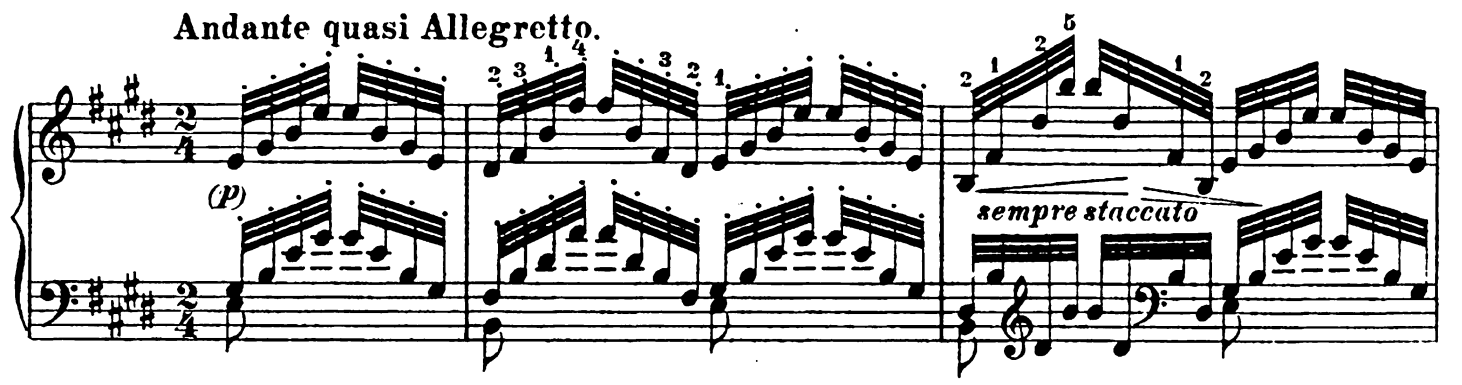

The third etude from the 1838 set is, for better or for worse, outshined by its revision, known as La Campanella. Like its popular brother, the third etude from the 1838 set uses the bell melody from the Rondo of Paganini’s second violin concerto. The staccato of the bell remains prevalent through most of the piece. The version present in the early Études d’exécution transcendante d’après Paganini is arguably more faithful to the original melody in style and articulative marking. It requires a different type of technique, generally involving big hands and extremely independent fingers, whereas the revised Grandes Études de Paganini version focuses on jumps and more traditional skills. Uniquely, the early version incorporates themes from the final movement of Paganini’s first violin concerto, melodies that are absent in the later version. Liszt does not stay faithful to the B minor key of the original Paganini work, but instead opts for G sharp minor, shifting the notes in large jumps onto the black keys, thus making them more manageable to play. Overall, this work maintains a highly playful and upbeat mood, contrasting with the revision’s more serious and mature approach typical of middle-aged Liszt.

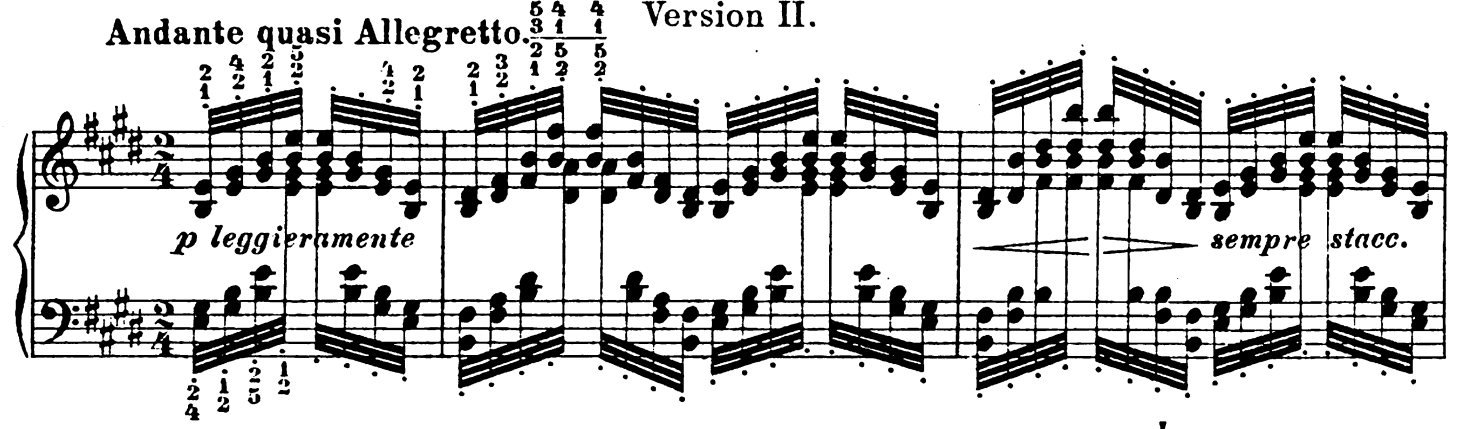

The fourth etude in the Études d’exécution transcendante d’après Paganini has, in the digital era, exploded to mythical status. The work itself is based on Paganini’s first caprice, which tests the violinist’s ability to bounce the bow off of the strings. Liszt provides two versions of the same piece: a first version labeled “4a,” which in itself is pretty challenging and tests the performer’s stamina and ability to move the fingers and arms quickly. However, the second version, called “4b,” is much more difficult, testing the abilities of the performer with large leaps and thick chordal writing. Many erroneously try to play this “4b” version at the speed of the original caprice, but Liszt’s tempo marking indicates that it shouldn’t be played nearly that fast. The version included in the 1851 set of études is much more refined, and the technique required is clearly intended to reflect the technique that the caprice features.

The fifth etude, “La Chasse,” is a beautiful and comparatively calm addition to the set, truly softening the otherwise firm and sometimes abrasive album. Initially a study on double-stops in the original ninth caprice, Liszt rewrites the voicing and lines to maintain a balance between faithfulness and effectiveness on a different instrument. A warm melodic line reminiscent of holiday music opens to a fiery passage evocative of the violin spiccato. The dolcissimo carries to the end, until the final chords are played with an awaking resolve and firmness. In the 1838 version, a much thicker texture is used, while the 1851 version is more laid back. The 1838 version includes an ossia which persists for nearly the entire étude, leading some to separate this early étude into two separate versions.

The sixth étude is based on the most famous of the caprices, number 24. The étude is structured as a theme with variations, similar to the original caprice. Many composers would later write variations on this same theme due to its versatility and recognizable rhythm. The 1838 version has some differences in the variations, but overall, the 1851 version of the étude is noticably improved in its voicing and texture.

In 1851, the Hungarian composer revised the early Paganini études into the Grandes Études de Paganini, S. 141. This set of pieces is stripped of the unnecessary difficulties of the early set, and includes many more refined textures and transitional sections. Like the S. 140 études, the S. 141 études are also dedicated to Clara Schumann. Renowned Liszt scholar Leslie Howard describes this relationship in the program notes of his recording of the études, writing:

“Liszt dedicated the 1838 set of studies to Clara Schumann and, for all her carping ingratitude, went on happily to dedicate the 1851 set to her as well.”

The ingratitude which Howard writes about refers to Clara Schumann’s strong distaste for Liszt’s compositional style, which she most notably expressed about these études and the Sonata in B minor.

The first and second S. 141 études are both remarkably similar to their predecessors. The motive and thematic material are identical, and the execution of pianistic prowess is visibly more refined. Liszt had, at this point, matured from his virtuosic early years in Paris. Living in Weimar as Kappelmeister, he truly honed his compositional abilities after his touring years came to an end. Here too we see the dilution of texture which is very common in Liszt’s constant process of revision.

The 1851 La Campanella could not be any more different than the 1838 version. Though it is just as technically demanding, the techniques used are quite different. The extended range in both hands and the articulative “capricious” tone present in the 1851 version contrasts with the 1838 version, which is more similar in style to the original Paganini study. However, the two versions of this étude are just some of the pieces composed after Paganini’s Clochette melody. Also among these compositions are the two large scale works numbered as S. 420 and S. 700i (a second version of this piece is catalogued as S. 700ii).

Out of the three versions, the fourth étude of the 1851 Grandes Études de Paganini is most consistent with the violin caprice. This version offers very few deviations from the original caprice in comparison with the two versions of 1838.

The fifth and sixth études do not have major differences between the originals and the revisions. The charges made are mostly improvements in texture, as well as the removal of unnecessary complexity not consistent with the character of the music.

Liszt’s two sets of Paganini études are very difficult works that require years of dedication and practice to perform well. The technical writing presented in these études is a testament to the magnificent Paganini, who took the world by storm with his incredible ability on the violin. Analysis of the differences between these works reveals Liszt’s incredible evolution as an artist and his ability to balance difficult technical writing with musical expression.