“For the virtuoso, musical works are in fact nothing but

Franz Liszt

tragic and moving materializations of his emotions;

he is called upon to make them speak, weep, sing and

sigh, to recreate them in accordance with his

own consciousness.”

Gradual cultural change captured the European musical landscape in the 1860s. The fervor of emotions and feelings from the previous decades subsided, and a classical-esque revival ensnared the zeitgeist of the new generation. The era of Early Romanticism (characterized by ideas such as expression over form and artist over audience) came to an end, and the musical community saw the emergence of late Romantic composers such as Wagner. Solemnness, earnestness, and a stricter adherence to musical structure replaced the extreme Romantic ardor of the years when Liszt extensively toured (which was primarily a byproduct of Beethoven and the broader artistic/literary Romantic movement). Liszt himself was a changed man, too. He had already retired from the concert stage for a decade and a half, focusing primarily on composition and losing much of the celebrity fame that the earlier “Lisztomania” movement brought him.

After moving to Rome from his musically tenacious home of Weimar in 1861, Liszt began freely experimenting with musical techniques. Liszt was no longer the man who thoroughly adored the sensualities of life (namely, love for fame and women). His good friends and lovers from his early adulthood, including Chopin and Marie d’Agoult, were merely fragments of Liszt’s past. He thus sought out Rome as a haven to freely release the thoughts of his troubled mind in the form of music and to seek the permission of the papacy to marry Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein, with whom he had maintained an adulterous affair for the past 20 years.

One great music staple exemplified by this transitional period is the Zwei Konzertetüden S.145 (“Two concert etudes”) set, which stands as a thematic and stylistic precursor to decidedly “late-Liszt” pieces. The beauty of these two etudes stems from the fact that echoes of bravura characteristics (remnants of Liszt’s style in Weimar) still come out in passionate runs, and yet feel distinctively restrained, as if foreshadowing the proto-Impressionistic ideals of the famous “Nuages Gris” S.199 (“grey clouds”) or “Bagatelle sans Tonalité” S.216a (“Bagatelle without tonality”).

Liszt was fickle with marking the purpose of the Two Concert Etudes. The set of two piano works was dedicated to Dionys Pruckner, a student of Franz Liszt from a decade earlier in Weimar who had begun his own touring and had assumed the role of pedagogue at Stuttgart Conservatory. The dedication, however, is markedly confusing because the pieces were intended for Ludwig Stark and Sigmund Lebert, both piano professors and co-founders of the Stuttgart Conservatory. Liszt composed the pieces for the duo’s Grosse theoretisch-praktische Klavierschule, a piano method famous at the time, which was translated into multiple languages and printed throughout Europe. Though published in 1858, it gained fame especially in its fourth edition format in 1870.

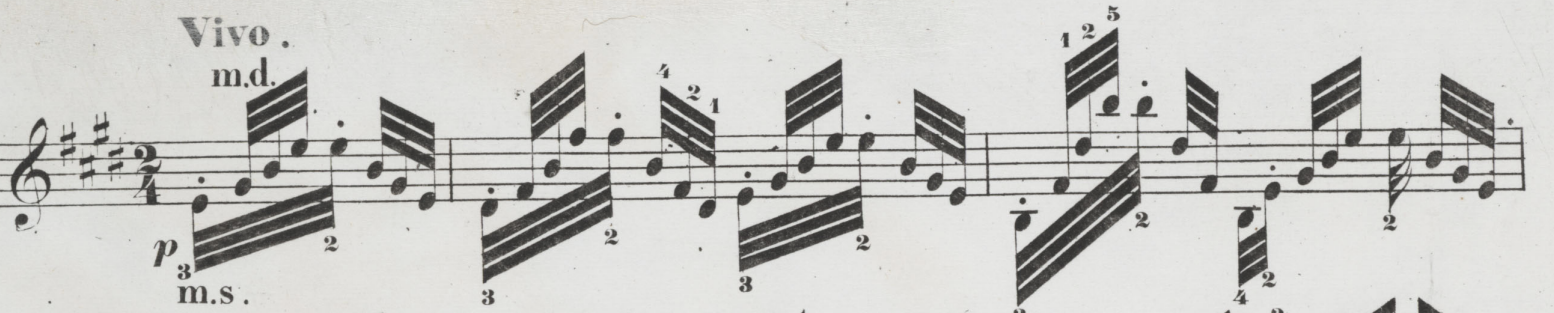

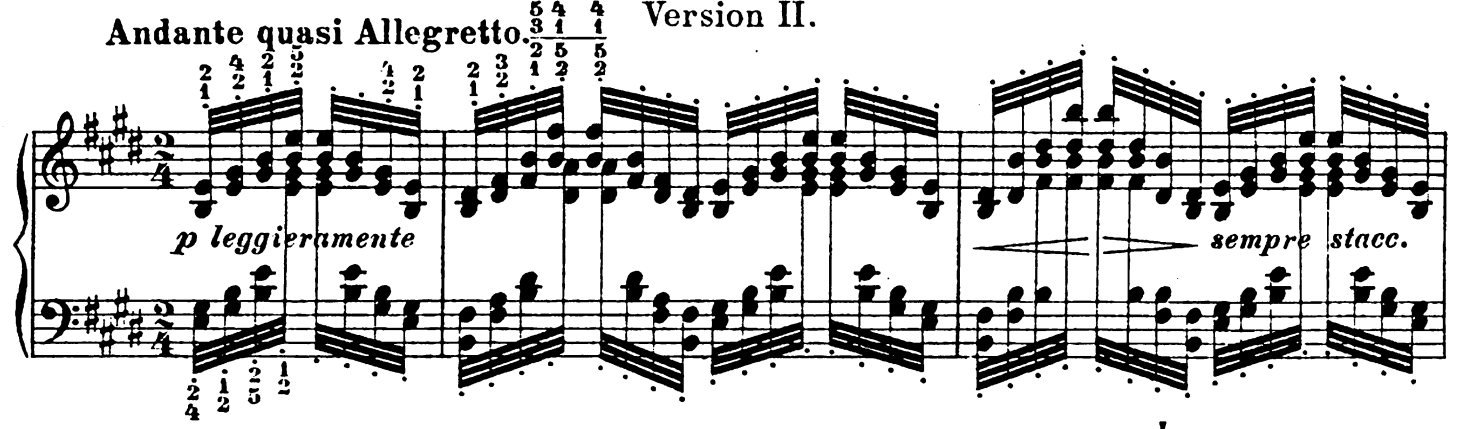

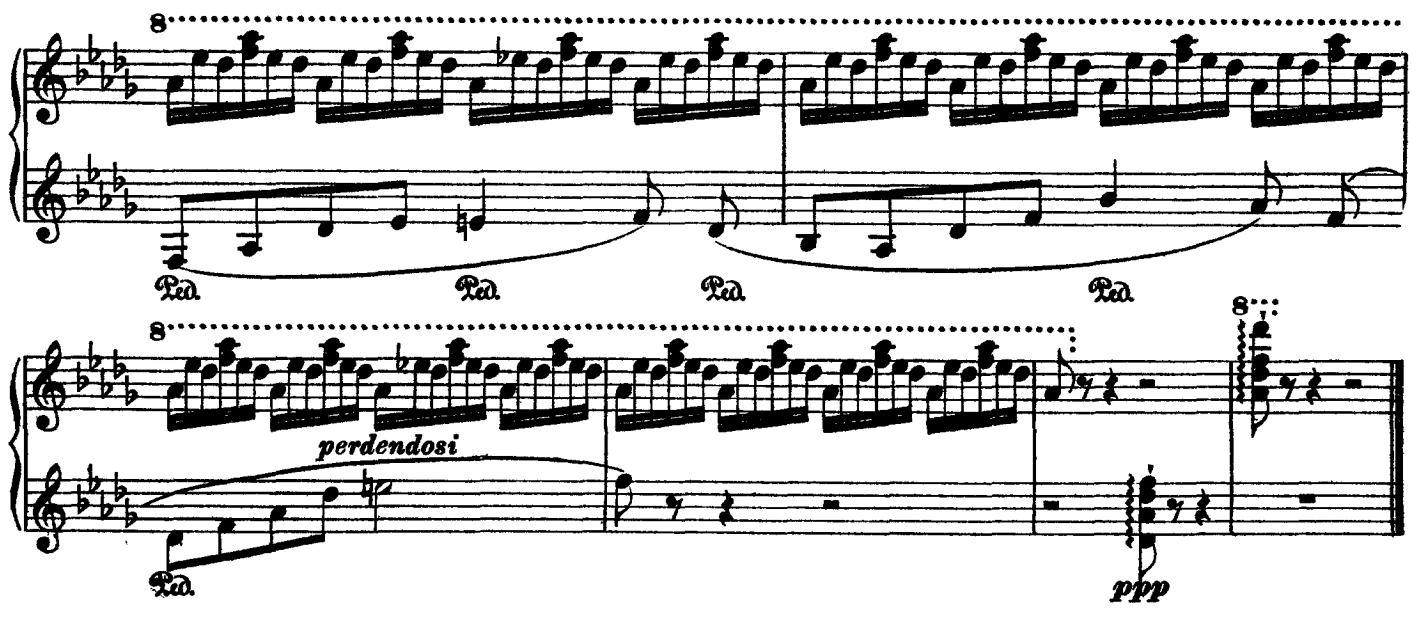

The first piece in the set, “Waldesrauschen,” is the lesser-played of the two and is in D-flat major. The piece is actually quite beautiful, evoking strong imagery of wind echoing throughout the forest. In some ways, it is similar to the earlier “Au lac de Wallenstadt” from the first Années de Pèlerinage S.160. Its title translates to “forest murmurs.” The tempo marking is “vivace,” and yet most recordings take it quite slowly. Like most romantic etudes, “Waldesrauschen” transcends the typical classical-era interpretation of the style (which often followed the etude’s literal meaning of “study,” emphasizing mechanics and the development of near-robotic technique). And yet, behind the flowing song-like melody in the left hides a secondary purpose for the piece’s composition: the repeating right-hand accompaniment that builds individual finger control. The voices then swap hands, with the ever-constant humming harmony echoing in the left hand and the melody strengthened as octaves in the right.

The developmental middle section brings a dramatic turn to the music: decisive, passionate octaves in the right hand resonate with the extremely cadential left hand, which rapidly ascends and descends. The techniques and phrasing used in this part draw connections to Liszt’s B-minor Sonata S.178, which was written nearly a decade ago, thus placing this composition firmly in the crossroads between the Weimar age that musicologists deem as Liszt’s golden era of composition and his late phase. Then, at the end, Liszt has the right-hand accompaniment fade slowly away, ending with a ppp rolled tonic chord in the middle register, followed by an even softer tonic “murmur” in the upper register. The similarities of “Waldesrauschen” to Liszt’s other sentimental middle-late compositions remain quite uncanny. Characteristically, Liszt’s “Waldesrauschen” features the common usage of the sixth chord, which Liszt employed in many of his introspective, often religious compositions.

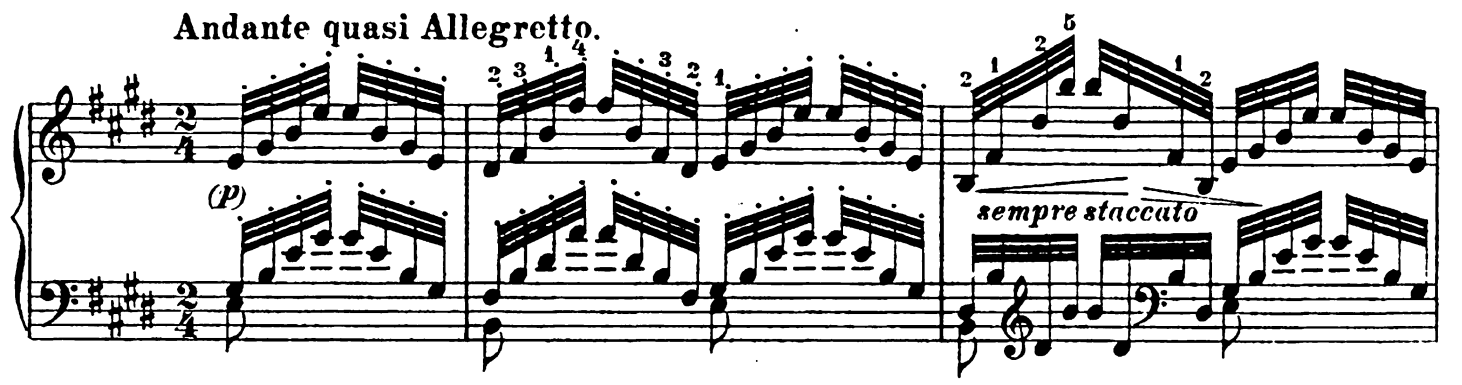

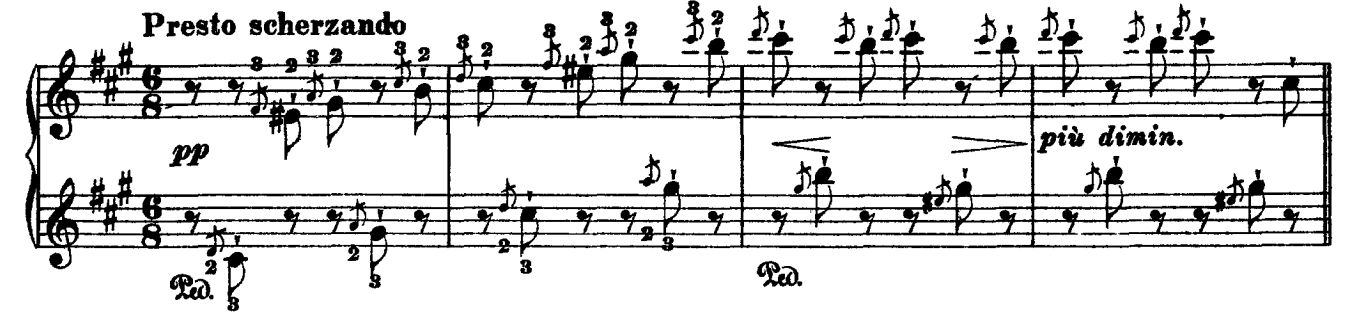

“Gnomenreigen” serves as quite a contrast to its previous companion. Pianists choose to perform it in concerts and competitions due to its technical difficulty. The translation of the title (“Round dance of gnomes”) suggests the imitation of magical creatures known to be stout, light, and yet quick. The tempo marking reflects this sentiment: “Presto scherzando.” Not only does Liszt require utmost speed, but he also insists on maintaining the scherzo-like nature of gnomes, which ultimately entails lightness and precision amidst fast passages. If it was not obvious enough, the fifth measure marks “staccato e leggierissimo,” meaning “detached and very light,” which verifies Liszt’s intentions. The piece’s central theme begins in F-sharp minor, emphasizing quick grace notes. Liszt then elaborates this in an A-major variation with an exceptionally fast right-hand under the marking of “Un poco più animato.”

The first theme and its elaboration repeat in B-flat major in a similar fashion, and then the music suddenly takes a “dark” turn as the key follows suit into the relative minor: the passage dips into the bass-clef area in a mysterious and earnest development. The section contains 54 consecutive bass “D” notes in an ostinato manner. F-sharp minor then grows into a grand recapitulation of the second elaborative theme. Then the soft first theme suddenly swallows the piercing climactic passage, as if the gnomes were returning underground after their fanfare, and the entire composition were a dream. Yet notably, “Gnomenreigen” ends on a F-sharp major (the parallel major of the initial key!) ascending arpeggio, suggesting Liszt’s optimistic, upward-looking objective for it. Perhaps Liszt honestly did believe in the good luck of gnomes.

Luckily, unlike many of Liszt’s pieces, the Two Concert Etudes gained popularity for a short period of time and maintained a relatively favorable status even after their creator’s passing. Perhaps the Zwei Konzertetüden’s success arises from their combination of quintessential early romanticism with the proto-impressionist flair of the very late 19th century, making them musically and historically rich. The pieces are representative of a changing European musical landscape where music itself was no longer homogeneous: taste grew diverse and fragmented, and visionary artistic leaders established different schools of music that advanced Western music in their own ways (namely, Leipzig’s conservative school, Wagner’s New German School, and even the Russian kuchka). As Liszt’s popularity declined with the arrival of a new generation of piano virtuosos, he reached a level of emotional maturity and artistic development that fundamentally altered his musical output.