“But where of ye, O tempests! is the goal?

Lord Byron

Are ye like those within the human breast?

Or do ye find, at length, like eagles, some high nest?”

Franz Liszt settled in Paris in 1823 as a child prodigy after his brief but meaningful stay in Vienna, Austria, the once capital of music, to study under the wing of the famed pedagogue Carl Czerny. However, as the worlds of art and literature experienced the changes which came with the Romantic movement, so too did music move in a similar direction. Although the young Liszt learned a lot in Vienna, the capital of music in the early Romantic era was Paris, not Vienna. Liszt wished to study there and enter the Paris Conservatoire, but he was denied entry because he was a foreigner. Consequently, he was forced to study elsewhere and soon make a living with his talent. To rise to fame, Liszt needed to be different and to explore the limits of musical existence. The first year of the Années de pèlerinage, S.160, is a testament to that goal.

1835 was the year of Liszt’s elopement in Switzerland with his mistress, Countess Marie d’Agoult. Liszt was making his name in Paris, having formed strong friendships with other musicians such as Frédéric Chopin and Hector Berlioz. One of the results of this elopement was a daughter, named Blandine. The other result would be the Album d’un voyageur, S.156, supposedly named after a letter sent to Liszt by George Sand, Chopin’s lover, during the elopement. This letter, similarly called the Lettre d’un Voyageur, was incidentally published in the Revue des Deux Mondes for fortunate scholars of the present era to analyze. The Album was Liszt’s first major set of piano pieces. This was later revised in 1855 to become the well known Années de pèlerinage, Première année: Suisse, referred to in English as the “First Year: Switzerland.” This would not be the only year however, because later on, Liszt would write two more collections of pieces based on his other travels. These collections were named after Goethe’s famous novel Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship, whose sequel was initially titled “Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahre,” essentially meaning “Years of Wandering.”

Similarly to other predecessors like the Douze Grandes Études, S.137, and the Études d’exécution transcendante d’après Paganini, S.140, the Album d’un voyageur contains very different material than its later revisions. However, this Album, unlike the early étude collections, contain several pieces which simply are not present in the later revisions.

The Album d’un voyageur is divided into three “sub-albums.” The first, Impressions et poésies, contains a majority of the pieces found in the revised set. Scholars generally agree that this first sub-album is the most pertinent and influential of the three. The second, Fleurs mélodiques des Alpes, contains pieces meant to evoke various sentiments, ranging from serene, flowing melodies to upbeat and forward-looking march rhythms. However, this second sub-album also offers musicians a deeper insight into music that would ultimately be cut from the final Années de pèlerinage product. The music from both the first and second sub-albums creates an overarching contemplative narrative that settles perfectly into the ideals of Romanticism. The third subalbum, labelled Paraphrases, serves a completely different purpose however. The Paraphrases indeed serve not as works composed specifically to fit in with the Album d’un voyageur narrative, but actually were revisions of the early collection Airs Suisses. These would later be revised once again as the Morceaux Suisses. Of these three sub-albums, only the first two remain of high importance in the context of analyzing the first Years of Pilgrimage.

The first entry of the Album d’un voyageur, called Lyon, is not present in the Years of Pilgrimage. It was inspired by an ongoing silk workers’ uprising in the city of Lyon, France, and was dedicated to Liszt’s early mentor Abbé Félicité de Lammenais. As with many of the works in the Album and Années, Lyon comes with a prefatory excerpt: “Vivre en travaillant ou mourir en combattant,” meaning “Live working or die fighting.” The triumphant melody, the complex and sometimes whimsical texture, and the use of chromatic octaves evoke the quintessential style of early Liszt, which is evident in earlier works like his fantasy after Auber’s opera La Fiancee , numbered as S.385 in Searle’s catalogue. The second entry, called Le Lac de Wallenstadt, is clearly a predecessor to the piece of the same name found in the First Year of the Years of Pilgrimage. Le Lac de Wallenstadt is also one of the pieces that Liszt provides a literary excerpt with, which in this case is taken from Lord Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, Canto 3.

Generally, the early versions found in the Album d’un voyageur are less refined than their Années de pèlerinage counterparts. Analysis of the two versions of Au bord d’une source and Vallée d’Obermann clearly demonstrates that Liszt slowly recognized the importance of musical evocation over technical capacity during what Alan Walker calls the “Weimar Years” starting in 1848. The early versions of these two pieces contain passages that require incredible dexterity and large hands that would not only be unnecessary, but also detrimental to the motive of the music. This is exemplified in the frantic left hand texture in the early version of Au bord d’une source and a general increase in complexity and thickening of texture in the early versions of Vallée d’Obermann. Although these passages create remarkable harmonies, there are simply too many notes for the self-reflective and evocative character of the set. The widespread use of thicker technical passages in these early works occasionally generates an unnecessary heaviness most similar to the Études d’exécution transcendante d’après Paganini, such as in étude No. 4b Arpeggio, where interval arpeggios in both hands create an effect that, though impressive, completely disregards the jumpy nature of the original Paganini caprice. After all, the Album d’un voyageur is highly based upon literary works such as Lamartine’s Méditations Poétiques and, significantly, Lord Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage (quotations from Byron are directly supplemented in the original sheet music!), a work that explores the disconnection of the wanderer from society and the sublime power of nature, topics that follow romantic ideals and may not be perfectly summed up in music through overly complex technique.

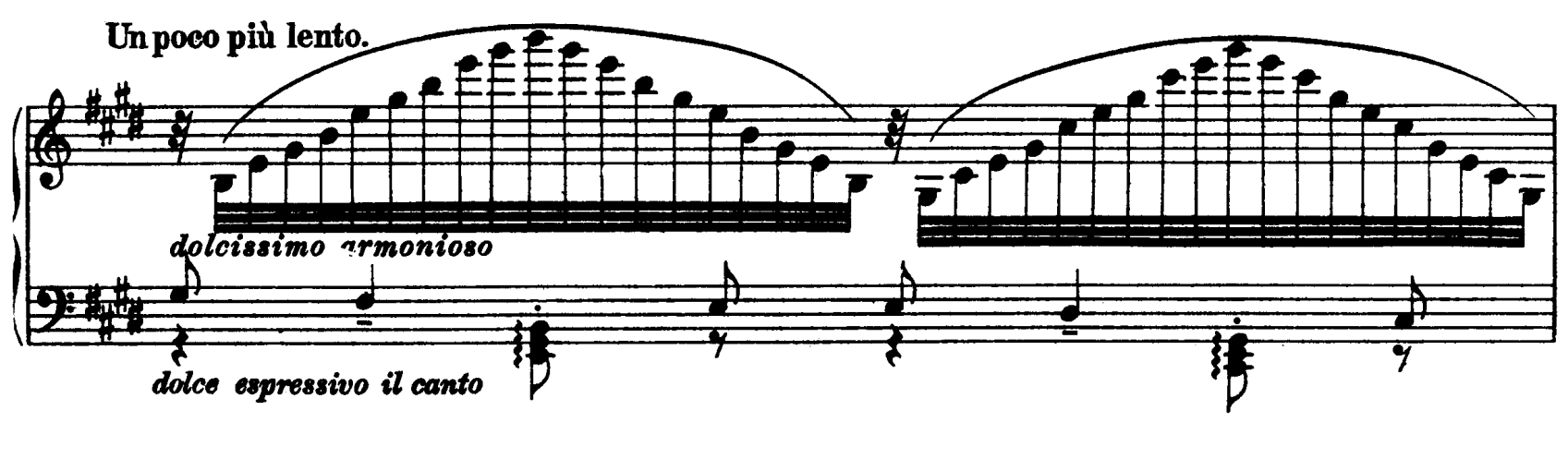

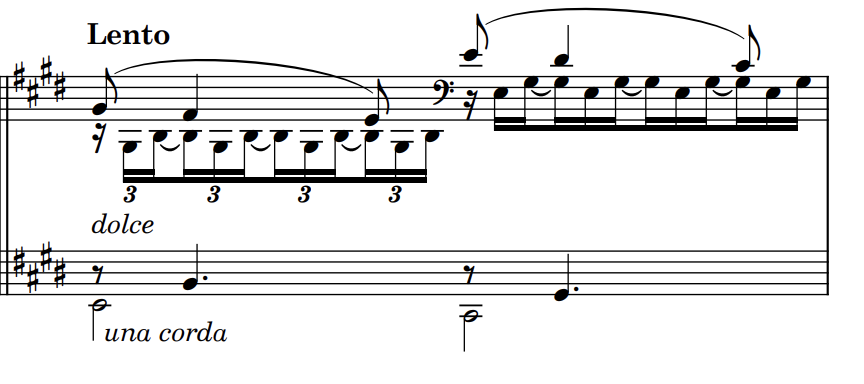

Of course, from this early revision came the now-famed first year of the Années de pèlerinage. This collection contains some of Liszt’s greatest original works, highlighting his capacity to compose and envision, rather than just paraphrase or transcribe works by other composers. In this new album, Chapelle de Guillaume Tell boldly introduces the works with a solemn lento followed by a horn call and echo meant to rally troops and encourage a struggle for freedom. Both Chapelle de Guillaume Tell and the second piece, Au Lac de Wallenstadt, were inspired by existing locations in Switzerland: William Tell’s chapel (and the story behind William Tell’s revolution) and Lake Walensee, respectively. The third piece, Pastorale, evokes images of bountiful vales and hills. The fourth, Au bord d’une source, is an excellent early example of how Liszt uses texture to depict flowing water. This theme would be revisited later in the third year of the Années. Here, Liszt masterfully employs a hand-crossing technique, which was famously championed by Scarlatti in the Baroque period and was once considered a bravura technique. There is a noticeable nuance in performance and subtlety in the use of complex techniques in the revised Au bord d’une source, which seems to have evolved from the upfront, nearly ostentatious display in the immature first version. Meant to induce imagery of a spring, the piece also comes with an excerpt from Schiller, a famous late 18th century writer who famously influenced Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” melody in the ninth symphony. The short excerpt reads:

“In Sauselnder Kuhle / Beginnen die Spiele / Der jungen Natur”

The poem takes a dark turn at the end, remarking on the irony of life and how the earth functions as a grave, but this motive is absent in Liszt’s musical rendition. Liszt would later add seven bars that echo and fade slowly to the end of Au bord d’une source, thus creating a third version that is virtually unknown. The inclusion of literary excerpts is also mirrored in Liszt’s teaching and transcriptions. Liszt was known to often connect pieces of music to literature, and he asked his students to do the same. In his transcriptions of Schubert songs, this desire is also reflected with the strong persistence to include the song’s lyrics next to the melody, rather than at the beginning of end of the book. While his publisher wasn’t always on board with this idea, it demonstrates Liszt’s desire to communicate a story through music.

It is hard to imagine a greater contrast between that and the fifth piece, Orage. Perhaps the most technically demanding piece of the nine, Orage stands as a sharp disparity from the previous four, abandoning all glimmers of hope and serenity for a tempestuous wave of anger and anguish. The sixth piece, by far the most often performed, is the infamous Vallée d’Obermann. What began as a piece not far off from Liszt’s operatic fantasies, found in an early form in the Album d’un voyageur, now becomes a shockingly tonally-complex masterpiece that has entirely sacrificed its own excessive technical difficulties for the sake of musicality. Based on Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage and Étienne Pivert de Senancour’s Obermann, Vallée d’Obermann captures the essence of Romantic existentialism and paints the picture of a man living in an isolated Alpine valley searching for his purpose in a chaotic world. What beings as melancholy tumbles into despair, until finally, after a long musical development that mirrors contemplation, the music falls into a beautiful and vocal melody triumphant over revelation. While we did briefly describe the piece and its background here, Vallée d’Obermann truly deserves an article of its own.

Eglogue, the seventh entry, is fairly similar to Pastorale in style, suddenly turning from the dark motive of the previous piece into a bright, hopeful melody that grows as the gray clouds open up to the sun. The eighth entry, Le mal du pays, centers on homesickness as Liszt yearned for the public life he once had in Paris. The ninth and final piece of the first Années is Les cloches de G*, initially included in the Album d’un voyageur. The original publication of this piece redacted the last few letters of the name, hence the asterisk. Musicologists have deduced that the full name of the piece was meant to be “Les cloches de Genève”, meaning “The Bells of Geneva.” This redaction was supposedly intentional, and it is believed that Liszt removed the name of the city to protect the privacy of himself and his mistress, Marie d’Agoult.

Many of these pieces can be analyzed through the literary excerpts that Liszt provides with the music. The composition of Album d’un voyageur was a big stepping stone for Liszt, indicating the onset of emotional maturity and understanding of life. The revision into the first year of the Années de pèlerinage, one could argue, was an even bigger landmark. During his time teaching in Weimar, Liszt’s music slowly transformed, beginning the process of spirituality and contemplation that he would embrace as his old companions, beliefs, and memories left the mortal realm. The beauty in the Années is the mixture of both pessimistic and optimistic sentiments into a wondrous story of life, despite many struggles and hardships Liszt faced as the world fell apart.