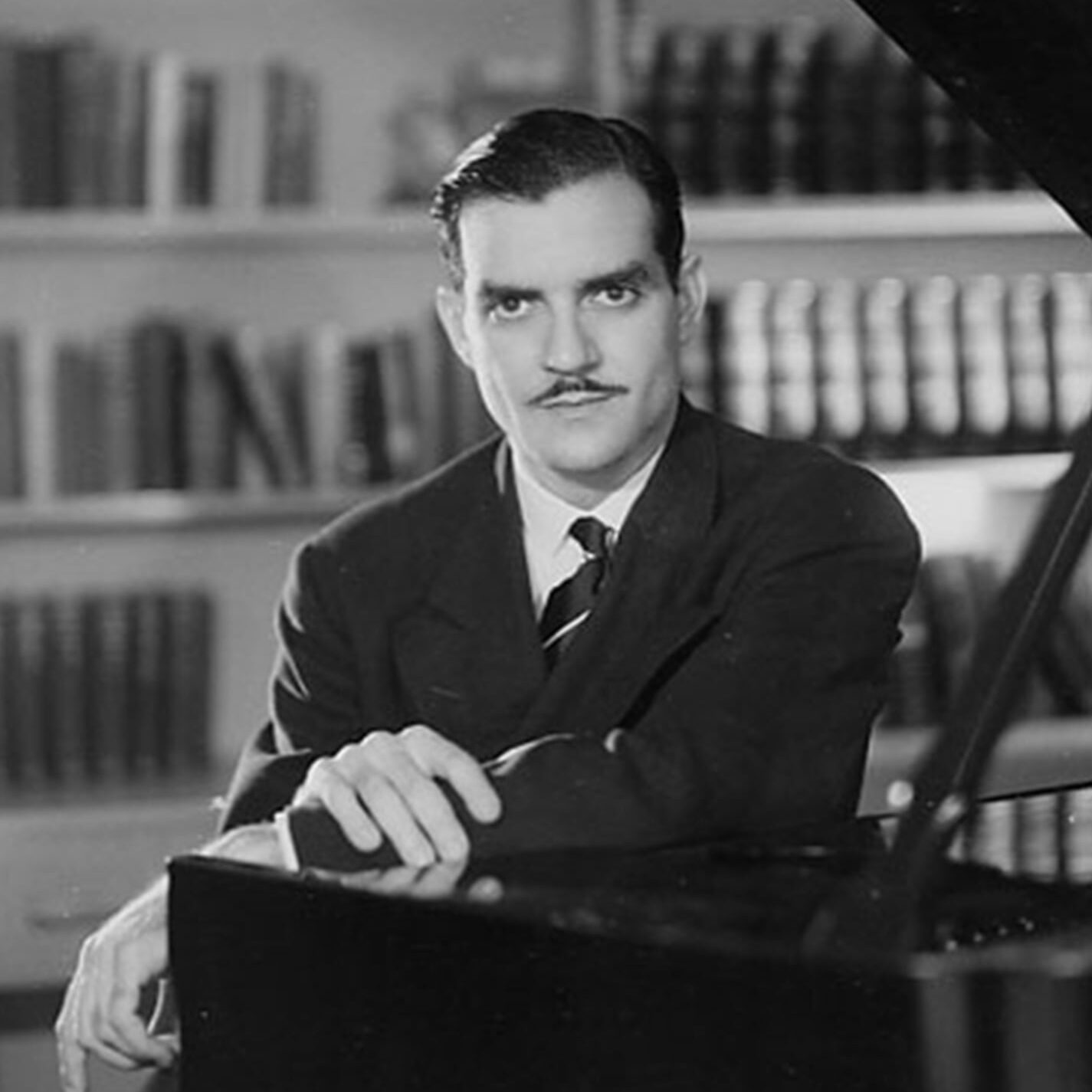

“Mournful yet grand is the destiny of the artist.”

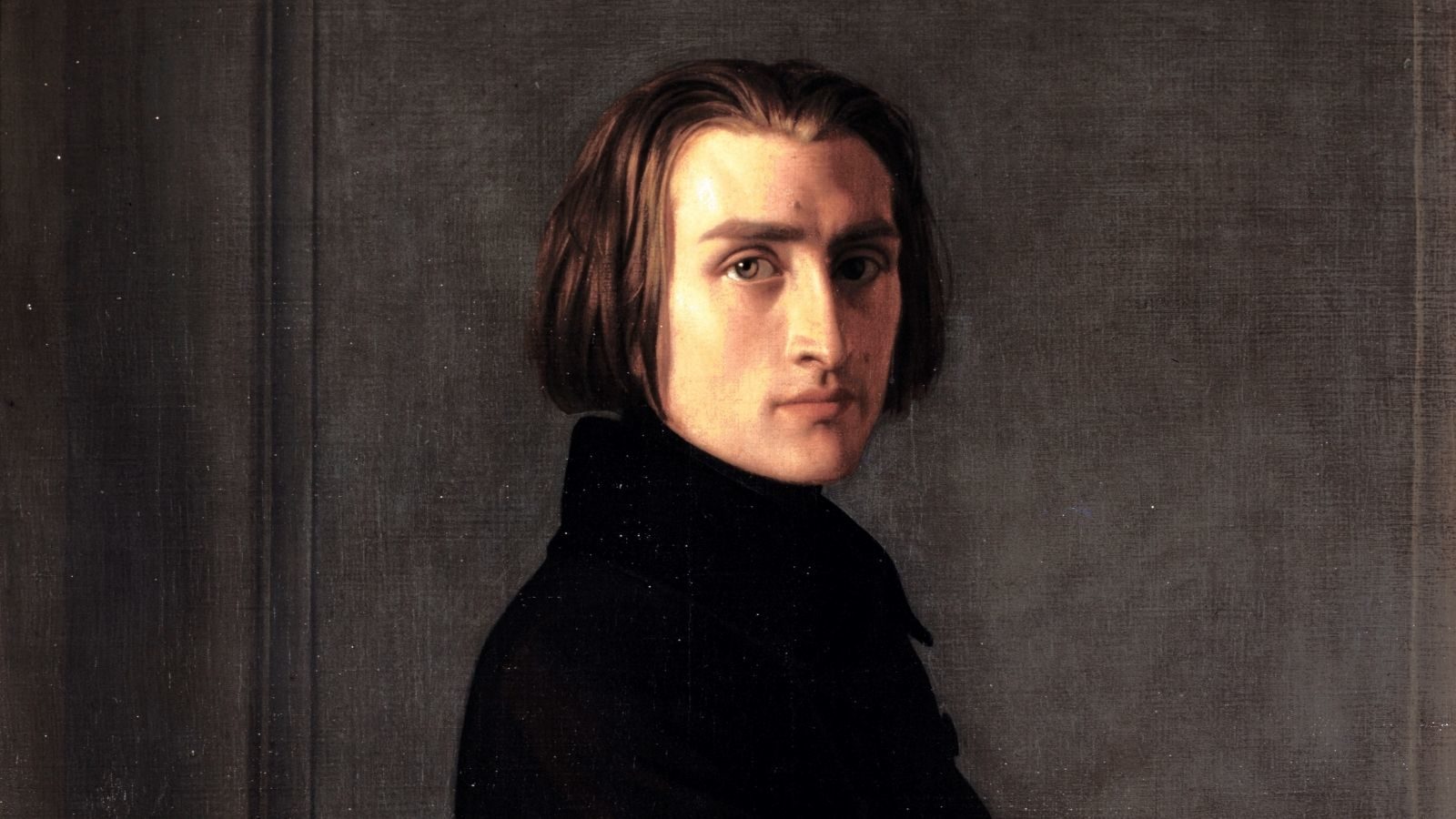

Franz Liszt

Liszt is a monumental figure within the piano world, and his reach extends far beyond his music. The personal struggles and social turmoil Liszt endured represent a musician who understands his work on a transcendental level. Grand and yet mournful, indeed, was Liszt’s life. One of the most unfortunate aspects of Liszt’s life was that he never found his true identity. Yes, he became a famous child prodigy during his education in Vienna and his early career in Paris. True, his music was staggeringly complex and challenged the very boundaries that separated performance from apotheosis. Equally valid is the statement that claims Liszt became a sort of mysterious, taciturn figure in his late years. But from the eyes of the man himself, he was a sort of Radagast, as one Lord of the Rings fanatic may say, blessed by God and sent to Earth with one purpose in mind, but never accomplishing that one purpose due to the vicissitudes of life. Unlike Radagast, however, Liszt never lost sight of that purpose, and he was never consciously and willingly distracted. Just like a man living within a cage of monkeys, the genius is judged by those who do not understand higher intellect or true dedication to life’s work. Such trapping and prejudice inevitably encourage faults on the genius’s path towards revelation, and in this case, Liszt truly and unfairly suffered. After all, even the wisest of men cannot help the feral monkey come to reason.

At the onset of Liszt’s career, the man was no more than another new musician coming into an industry already firmly established. Beethoven was the greatest genius of all time. Hummel composed the grandest of piano concertos. Liszt was a child prodigy trying to create a name for himself, who just moved from Vienna (a musically dying city) to the heart of European Romanticism: Paris. His class would also have been severely restrictive for his music education if it had not been for the diligent work of his father, Adam Liszt, who secured the blessing and patronage of Prince Nikolaus Esterházy II, a prominent Hungarian royal who just so happened to love classical music.1 As with any up-and-coming working man, connections mattered if one wanted to climb the rungs of the social ladder. Such connections started with the acquaintance of Frédéric Chopin and Hector Berlioz. Europe had just seen a successful touring virtuoso, the mythical Niccolò Paganini. With his retirement, who would come next to rock the continent to its core? Liszt aimed to be that man.

The composer faced numerous challenges throughout his life. During these early years in Paris, the stubborn and tenacious Revue musicale, a popular musical newspaper run by famously obstinate critics, refused to let a rookie become the subject of the headlines.2 It did not help that Liszt was the matter of controversy due to his unique personality. The most remarkable example was his affair with the married Countess Marie d’Agoult.3 Their elopement to Switzerland during the summer of 1835 caused so much shock that Liszt’s public image was effectively ruined. Liszt was also rather judgmental, and in 1837, he published an unfavorable public review of another highly prominent pianist, Thalberg.4 Soon, the two scheduled a “duel” at the salon of Princess Cristina Trivulzio di Belgiojoso (allegedly, Marie d’Agoult wrote the review and used Liszt’s name, but what is certain is that Liszt agreed to the duel). This duel became the talk of the town, with newspapers inflating the story to epic heights. Opinions on the result of the duel were mixed at the time. Still, it is generally agreed in the modern day that, as biographer Alan Walker puts it, “Liszt received the ovation of the evening and all doubts about his supremacy were dispelled. As for Thalberg, his humiliation was complete. He virtually disappeared from the concert platform after this date.”5 Clearly, the press could, and would, be an issue for Liszt’s reputation and career.

In the modern age, it is easy to share cultures and ideas quickly with the internet and social media. However, in the early nineteenth century, no technology existed for the masses. Liszt could not simply build his reputation as a prodigious composer in Paris and then have a grand reception elsewhere where he would be hailed as a hero. In fact, when Liszt dared venture down to Italy, nobody knew about him, and nobody cared for his music (south of the Alps, opera dominated).6 The genius would have made a name for himself not just in his base of operations, but also everywhere he plans to compose and perform. The lack of connection between thinkers of different places also isolated scholars by nation, exacerbating nationalistic thinking and fostering conformity. Liszt was famously a non-conformist, revolutionizing the approach to music and diversifying repertoire (read here). Thus, another clash between the musical genius and society.

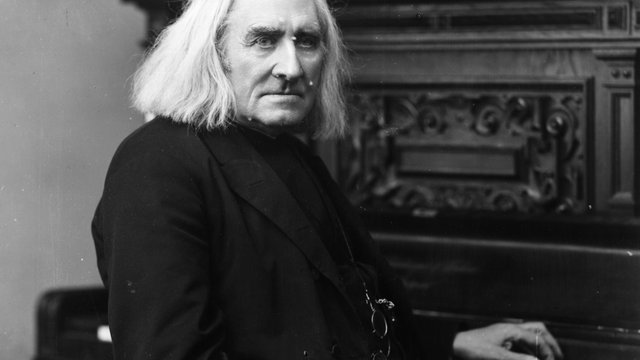

Late in his life, Liszt became deeply religious. Interested in the spiritual and divine, his works became less virtuosic and programmatic, turning towards surrealism and symbolism. The drastic shift is evident in his late pieces, which hint at atonality and harmonic divergence that would become the hallmarks of 20th-century impressionism.7 French and German titles for works gradually turned into Latin titles. Liszt also began to delve more deeply into choral pieces, both secular and sacred.

Both these inner turmoils and external pressures emotionally tore Liszt apart, but it was his resilience, brilliance, and innovation that held it together. Unfortunately, Liszt passed away in 1886, during the peak of his spiritual maturity and his journey toward musical “deification.” He left without having ever fulfilled his ultimate goal, that is, to reach the apotheosis that could have been aroused within himself. His text on harmony was not yet finished and has been lost to time. Liszt may not have been content with his achievements in life. Still, it would make him feel fulfilled if the next generation of musicians appreciated his efforts and contributions to society.

1Walker, Alan. Franz Liszt, The Virtuoso Years, 1811-1847. 1983, 64-70.

2Liszt, Franz. An Artist’s Journey. 1989.

3Short, Michael. The Liszt-d’Agoult correspondence. 2013.

4“La Gazette musicale de Paris,” March 20, 1837.

5Walker, Alan. The Great Composers: Liszt. 1973, 40.

6D’Agoult, Marie. Mémoires. 1879.

7Walker, Alan. Franz Liszt, The Final Years, 1861-1886. 1996.

Further reading

For further reading, peruse the Sources page. There one will find the gold standard informative books, letters, and essays regarding Liszt’s musical and historical study.

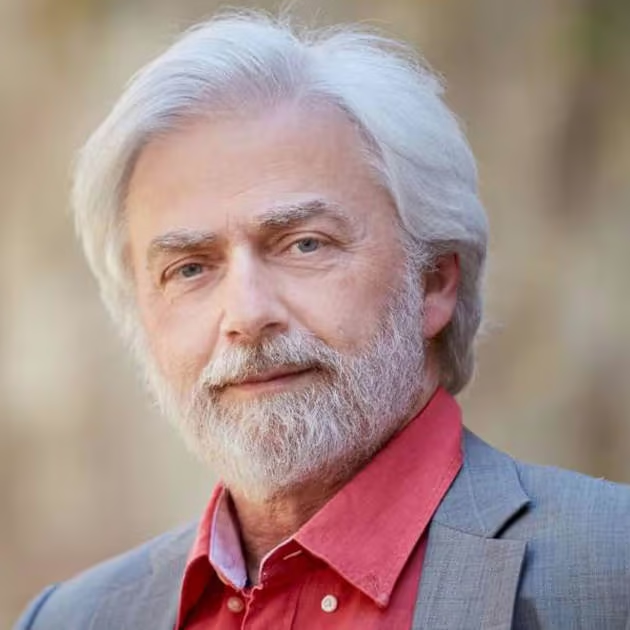

The best Liszt interpreters

Vladimir Horowitz

Changes lots of notes for his own interpretation, but is a fantastic Liszt performer. Not just one of the “greatest of all time” for Liszt, Horowitz stands as a beacon for all musicians.

György Cziffra

The definitive Liszt interpreter. Cziffra’s playing is grand and undoubtedly unique. Cziffra did rewrite many passages, making his recordings particularly helpful only after one has learned the piece oneself.

Cyprien Katsaris

Overall, a phenomenal pianist for all sorts of works, but his recordings for Liszt can be described as virtuosic and fervent, yet delicate when necessary.

Krystian Zimerman

Not only is it famous for Chopin, but it is also unique for Liszt. He has excellent power and control, especially in significant works such as Liszt’s B-Minor sonata and Totentanz.

Stephen Hough

Hough’s recordings of Liszt’s works can be described as vocal. His effortless performance of complex passages is quite astonishing. Hough also demonstrates extreme stamina in his playing, never missing the beat.

Claudio Arrau

Arrau’s interpretations of Liszt repertoire have always been unique (and sometimes criticized), but his emotional and near-spiritual takes on voicing and pace are extremely praiseworthy.

Leslie Howard

Famous for recording all solo piano works by Liszt, a monumental task. Some of his recordings leave a lot to be desired, but one of Liszt’s relatively unknown/niche works is surprisingly good.

Jorge Bolet

Sophisticated and lyrical performances, combined with raw power, lead Bolet to wield tremendous skill in Liszt. Definitely old-school style.

Other notable pianists for Liszt include: Lazar Berman (Années de Pèlerinage, especially), Goran Filipec (for first versions of works, such as the Transcendental Paganini Etudes), Jeno Jando, Andre Laplante, Marc-Andre Hamelin (for pieces with virtuosic tendencies), Evgeny Kissin, William Wolfram (operatic fantasies), Daniil Trifonov, Endre Hegedűs (operatic fantasies), Ferruccio Busoni (all of the few recordings he has), Boris Berezovsky, Sviatoslav Richter, Grigory Sokolov, Enrico Pace, Earl Wild.

Popular Piano Pieces

Generally, in order of popularity, top to bottom.

- La Campanella S.141/3

- Hungarian Rhapsodies (S.244/2, S.244/6, S.244/12)

- Liebestraume S.541/3

- Consolation S.172/3

- Un Sospiro S.144/3

- Concerto No. 1 S.124

- Mazeppa S.139/4

- B Minor Sonata S.178

- Feux Follets S.139/5

- Après une lecture du Dante : Fantasia quasi sonata S.161/7

- Chasse Neige S.139/12

- Ballade No. 2 S.171

- Vallée d’Obermann S.160/6

- Paysage S.139/3

- Bénédiction de Dieu dans la solitude S.173/3

- Mephisto Waltz No. 1 S.514

- Gnomenreigen S.145/2

- Reminiscences de Don Juan S.418

- Spanish Rhapsody S.254

- Rigoletto Paraphrase S.434

Lesser-Known Piano Pieces

Generally, in order of accessibility and speciality, top to bottom. These are just a few of a very long list; the ones included here are provided as examples, in hopes of inspiring one to delve deeper into the repertoire.

- Sposalizio S.161/1

- The Reminiscences:

– Reminiscences de Lucia di Lammermoor S.397

– Reminiscences de Robert le Diable S.413

– Reminiscences de Lucrezia Borgia S.400

– Reminiscences de Boccanegra S.438

The Reminiscences make up a large part of Liszt’s operatic fantasies. None of the themes used is an original composition by Liszt. All the pieces that form the Reminiscences are very different in scale, nature, and even date of composition, so they are not traditionally considered as a “set” by the Searle numbering system. There are many versions of each opera fantasy, typically differing only slightly.

- Tannhauser Overture S.442

- Beethoven Symphony Transcriptions S.464

- Liebestraume S. 541/1

- Douze Grandes Etudes S. 137

- Études d’exécution transcendante d’après Paganini S. 140

- Glanes de Woronince S. 249

- La Sonnambula Fantasy S. 393

- Beethoven’s Turkish Capriccio S. 388

Liszt scoring YouTube channels

- Andrei Cristian Anghel

- Ashish Xiangyi Kumar

- PianoJFAudioSheet

- Chocho Angel

- Bartje Bartmans