“It was with a heavy heart that Liszt embarked

Alan Walker

on his six-month tour of the Iberian Peninsula…

Liszt was the first and certainly the greatest

virtuoso to roam freely through Iberia.”

Liszt’s relationship with Countess Marie d’Agoult was over by the time he decided to tour the Iberian Peninsula in 1844 and 1845. The relationship, against all odds, lasted over a decade. Despite frequent periods of separation due to Liszt’s hectic concert schedule, the two managed to stay together, potentially because absence often fosters intrigue and excitement, stretching the relationship to its limits. In any case, when Marie d’Agoult expressed her feelings about Liszt’s insufferability regarding music in her novel Nelida, it created a rift so great that no pangs of sentiment could ever bring the two together again. Liszt already had deteriorating health going into the Iberian tour, stemming from relentless performances and practicing, as well as an ongoing feud over parental authority regarding Marie d’Agoult and her children.

Franz Liszt was truly the pioneer of virtuosic piano performances in Spain and Portugal, with his famed rival Thalberg arriving in 1846, followed by Gottschalk in 1851 and Herz in 1857. Arriving at the Teatro del Circo in Madrid, which had recently been converted from a hippodrome to the center of Italian opera in Spain, Liszt gave four concerts. The program primarily consisted of operatic transcriptions by Bellini and Donizetti, echoing the venue in which they were performed. Soon after, he would visit Lisbon for more performances, but Portugal would not have as significant an impact on Liszt’s catalogue as Spain’s diverse and seemingly exotic musical culture did. Five pieces were inspired by this tour of Spain: Rhapsodie espagnole, S.254, Rondeau fantastique sur un thème espagnol, S.252, La Romanesca, S.252a/S.252b, Romancero Espagnol, S.695c, and the Grosse Konzertfantasie über spanische Weisen, S.253.

The best method of analysis is to follow the composition date, as all Spanish pieces are related in some way, with each new composition borrowing from its predecessor and incorporating new, and often more refined, techniques and pianistic details. It would be incorrect to call them revisions of the same piece however, as they are structurally and fundamentally different. La Romanesca would not only spark Liszt’s interest in Spanish folk tunes and themes but also contribute to the popular movement throughout all of musical Europe. This interest would grow and evolve into a distinct form of piano music, incorporating the style of Spanish music rather than true and pure Spanish folk music. Of course, easy to name composers after Liszt who jumped onto the trend include Moszkowski and Bizet, whose Caprice Espagnol and Carmen, respectively, are characteristically Spanish in nature but aren’t truly Spanish (the composers themselves are German and French!). For some strange reason, La Romanesca was for a long time considered to be inspired by Italian culture and style, as the title of the first publication read “fameux air de danse du seizième siècle” or “famous dance tune from the sixteenth century,” which really does not say anything at all.

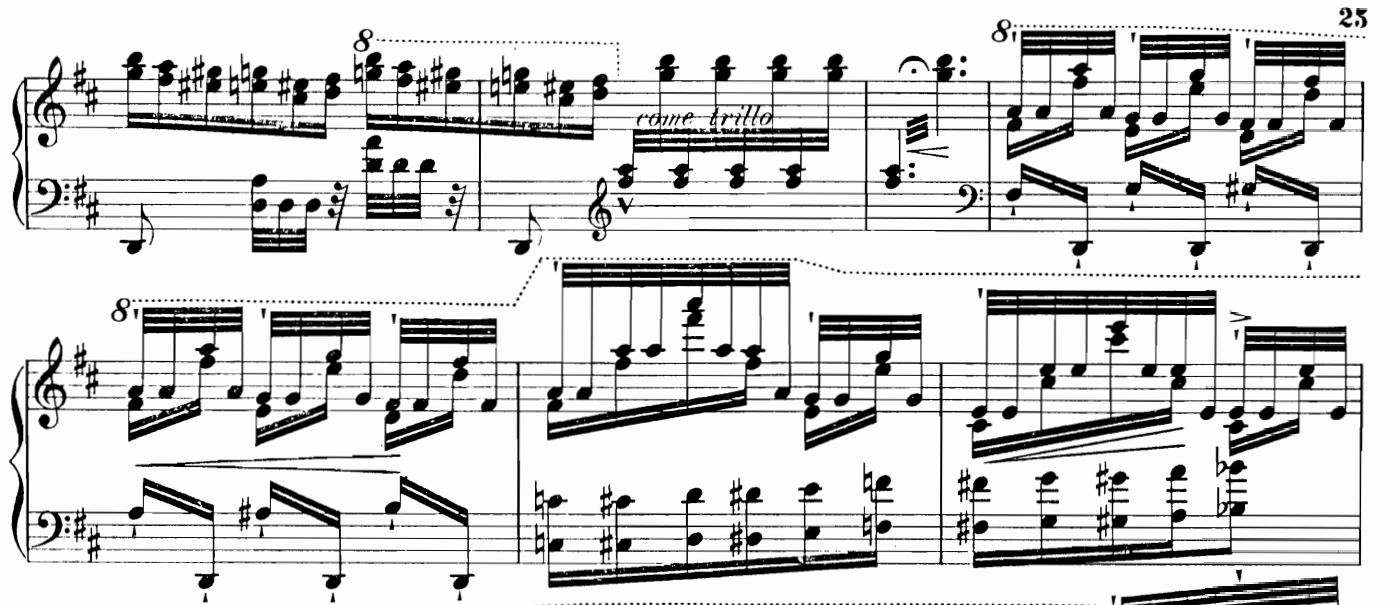

Published in 1840 but written a few years earlier, the first version of La Romanesca primarily uses a 4/2 time signature, with a bit of 3/2 in the introduction, something not often seen in secular Liszt works. A relatively calm and collected work, La Romanesca elaborates on a familiar-sounding Spanish-style theme, incorporating a plethora of trills stereotypical of Spanish music. The second version, catalogued as S.252b contrasts with the first version mainly with its lighter texture and ornamentation. The revision is less clouded with thick chords and generally lighter in feel, most notably with the staccato left hand in the exposition after the introduction. It is also in a more commonly used 3/4 time signature. In addition, the second version includes an entirely different coda.

The second piece in the Spanish catalogue of Liszt works is Rondeau fantastique sur un thème espagnol, known popularly as “El Contrabandista.” Based off of a very popular Spanish tune at the time, an aria from Manuel Garcia’s one-act opera El poeta calculista called “Yo que soy contrabandista,” Liszt published the work with a dedication to Chopin’s lover George Sand in 1837, accompanied by the famous Grande fantaisie de bravoure sur La clochette, S.420, as well as Fantaisie romantique sur deux mélodies suisses, S.157. Of course, as with the “La Clochette Fantasy” and many of the other harrowingly difficult early Liszt works, “El Contrabandista” is not played often, receiving very few recordings to date. Liszt himself planned on using it as a finale for recitals, but he barely used it in performance, favoring other pieces such as Reminiscences de Lucia di Lammermoor, S.397. The composition features repeated notes that require high stamina and precision.

Romancero espagnol, or “Spanish song-book,” as with “El Contrabandista,” is also rarely performed. The piece, attributed to a composition date in 1845, was never finished or published in Liszt’s lifetime. Supposedly, from analysis of Liszt’s letters, the “Spanish song-book” was meant to be published in 1847 with a dedication to Queen Isabella II of Spain, but the publication never took place. Unfortunately, the ending was not fully perfected, and essential parts were left blank, as is often the case with many of Liszt’s forgotten works. Romancero Espagnol is split into three sections: the first being the introduction and Fandango variations, which elaborates on a traditional Spanish dance. The Spanish tune itself is highly chromatic and ornamented, with many decorative aspects of the piece contributing to its overall difficulty. The second section begins after a glassy passage that is evocative of a tambourine and elaborates on an unidentified theme. This section is more serious and controlled than the other two. It is almost Baroque and fugal in style, with the melody “calling and responding” from one hand to the other. As with the transition between the first two sections, the transition from the second section to the third is rather abrupt. Though all three parts of Romancero Espagnol are distinct in melody and nature, they cannot be played separately due to unsatisfactory conclusions in the Intro and Fandango section and the elaborative section, and in the case of the final segment, which incorporates the famous jota aragonesa and coda, an unsatisfactory introduction. The third section is based on the same jota aragonesa that would later be reused in the Spanish Rhapsody.

The Grosse Konzertfantasie über spanische Weisen, while long forgotten, has recently garnered attention in online media. Published long after Liszt’s death and dedicated to Liszt’s biographer Lina Ramann, the “Spanish Fantasy” also uses three primary themes: a fandango loosely inspired from the fandango in the third act of Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro, a jota aragonesa, and a cachucha.

By far the most well-known of these Spanish pieces is the Rhapsodie Espagnole. This masterful piano composition encompasses all techniques within the traditionally popular Liszt standard repertoire. Standing as a contrast to Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsodies, the piece borrows melodies directly from both Romancero espagnol and the “Spanish Fantasy”. The piece itself alternates between variations on la follia and the well known jota aragonesa used by Liszt in his other pieces inspired by the Iberian tour. While it was published in 1867, Liszt actually composed the “Spanish Rhapsody” four years earlier while in Rome, long after his Iberian tour had taken place.

Another Spanish piece not included in the five mentioned earlier is Spanisches Ständchen: Mélodie von Grafen Leo Festetics S.487. This piece is not traditionally considered within the Liszt Spanish album because it is pretty much a direct transcription of “Spanish Serenade,” a song of one of Liszt’s supporters and friends, Count Léo Festetics, who was actually one of the few Hungarian aristocrats who sponsored Liszt in his youth as a touring young prodigy. There is simply not enough original material in the transcription beyond what is provided by the vocal rendition to consider it of Liszt’s own.

The Spanish album of Liszt will forever remain of paramount importance, embodying the common obsession with exotic music in the early 1800s. These pieces contain both passages that show off the performer’s technique as well as beautiful melodies that seem to bring the hills of Castile to the recital hall.